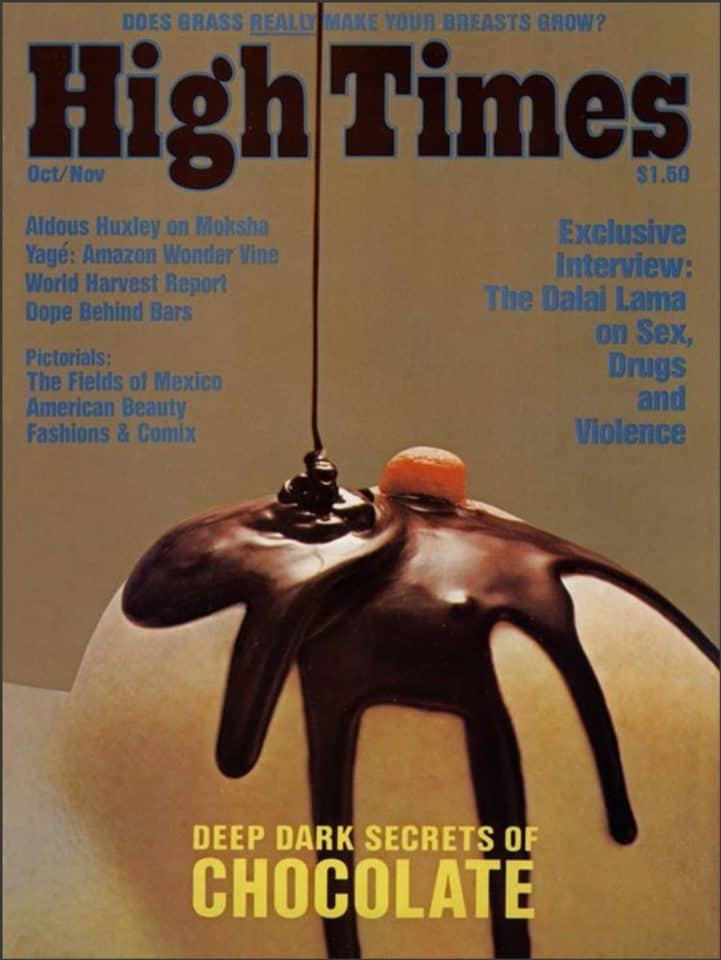

Each Friday, we’re republishing an article from the High Times archives. This week, we’re bringing you an article by Robert Lemmo, published in the October/November, 1975 issue.

Nineteenth-century America has oft been called “a dope fiend’s paradise,” owing to the fact that opium, morphine, cocaine, cannabis extract, nitrous oxide and various other neo-taboo highs were then freely and cheaply available to all comers. Modern dopers are apt to clench their nostrils in abject jealousy at the thought of their forebears sauntering down to the village greengrocer or corner apothecary to pick up an ounce of pure coke for $2.50—the price in New York at the turn of the century. The bubble burst in 1914 when the passage of the Harrison Act—a measure designed to keep the gentle weeds and helpful powders from the populace—drove thrill seekers to the street and prices to the ceiling. Luckily, chocolate slipped through the traps.

Chocolate, you ask? That treat for tots, that lozenge for lovers, that morsel for Mom? The very one. For, throughout its long history, chocolate has been looked upon as a delicious temptress, used not only as a food but also as a homicidal stimulant, a summoner of Satan and a devastating aphrodisiac. In “The Song of Right and Wrong,” G.K. Chesterton wrote:

Tea, although an Oriental,

Is a gentleman, at least;

Cocoa is a cad and a coward,

Cocoa is a vulgar beast.

For all its vulgarity, chocolate is an immensely popular beast. World cocoa production in 1973—74 was estimated at 1.45 million tons; in the United States alone, chocolate is a $2.1-billion-a-year industry. And far from being confined to the mundane rectangular chocolate bar, cocoa today manifests itself in a spectrum of chocolate imagery rivaled only by the chopped chicken liver sculptures of the New York bar mitzvah catering renaissance.

The present-day chocoholic may, for example, chew chocolate-flavored gum, smoke tobacco mixed with chocolate, roll joints with chocolate-flavored papers, drink cocoa wine and liquers, sniff choco incense or stink with chocolate perfume and massage oils, scarf down chocolate psychedelics (the so-called chocolate mescaline), stash away chocolate space sticks (a dried “energy food”), smear on a film of cocoa butter, crunch chocolate-coated ants, snort a dash of chocolate snuff, masturbate over chocolate nudes from Düsseldorf, even lick chocolate-sprayed genitalia. True chocolate addicts will even attempt to spend chocolate coins, write with chocolate pencils and ignite chocolate cigars. The great mystery is how this potent drug, once as psychoactive as any mushroom on the Mazatec menu, has come to be an economic and dietary staple in and out of Christendom.

Chocolate is a product of the cocoa bean, the seed of the evergreen Theobroma cacao, as the Swedish botanist Linnaeus named it in the early eighteenth century. Theobroma is Greek for “food of the gods,” which is how the ancient Aztecs referred to cocoa, their favorite aphrodisiac; cacao refers to the tree itself. Cocoa is the bean that springs therefrom, and chocolate is the product made by mixing cocoa butter with ground cocoa beans to make a smooth paste. The word “cocoa” sprang from European confusion between the cacao tree and the cocoanut palm, and like many errors, it stuck. Modern heads wishfully confuse cocoa with coca, the source of cocaine. Although cocaine comes from Erythroxylon coca, a totally different plant, these two gifts of nature do have one essential link: both produce an alkaloid that gets you off.

Cocoa beans are 2 per cent theobromine, a central nervous system stimulant that dilates the blood vessels of the brain and heart, dilates the bronchii of the lungs, stimulates the production of digestive juices and acts as a diuretic on the kidneys. In county jails, the prisoners’ commissary is delivered on Friday afternoon, and so much chocolate is eaten by cons at that time that no one can sleep on Friday night.

To varying degrees, chocolate shares these physiological effects with cocaine, caffeine and theine, the active component of tea. Cocoa’s advantage over the other common ingestible alkaloid plantstuffs is taste. Of chocolate, coffee, tea, coca leaves and let’s include betel nuts, chocolate surely has the richest taste. The sensation of the mouth being inundated with flavor, familiar to the chocolate hound, is caused by the strong stimulation of many taste buds, foremost among them a nerve called Krause’s end—a bulbous little nodule, extraordinarily sensitive to all kinds of stimuli, that is located mainly in the lips, mouth and penis or clitoris. Thus the oral attractiveness of chocolate is decidedly sexual.

In addition to this physiological link, the psychology of chocolate is bound to the concept of pleasure. Chocolate is one of the commonest reward-and-punishment devices used by parents who, otherwise careful to keep coffee and tea away from their tykes, blithely charge up young neurosystems with theobromine as a way of teaching their child the difference between right and wrong. And who among us does not recall Peter Paul’s Mounds candy bar commercial? Eight or ten times a day during our childhood TV addictions, we watched chocolate sensuously poured over the bar’s two breastlike almonds. Who, more recently, relished Ann-Margaret in Tommy, humping her hot-dog pillow after being sprayed with chocolate from her smashed television tube?

This kind of pleasure association gives chocolate that extraspecial kick of habituation—chocolate lovers will feel a genuine need for chocolate that nothing else can satisfy. In this sense, chocolate is as addicting to a large number of people—millions, probably—as are sex, cigarettes, roulette, cocaine, what have you.

And, to top it off, chocolate is good food. About 90 per cent of the cocoa bean can be digested, comprising 40 per cent carbohydrates, 22 per cent fat and 18 per cent protein. So chocolate, a cocoa product combined with sugar, is a quickly assimilated nourishing energy food—something which the Allies in World War II took full advantage of, plying fresh-faced recruits with bars of chocolate to ensure a high level of homicidal energy in combat. In America, chocolate became an essential wartime industry; manufacturers were given priorities on plant construction materials, equipment and supplies for making chocolate. And we won.

As with most of life’s basic pleasures, the precise origin of cocoa is unknown. The Aztecs, Mayans and Toltecs were busily cultivating the cacao plant over 3,000 years ago, however, and the Indians of South America still revere the ancient god of the air and high places, Quetzalcoatl, who brought cacao seeds to Earth from Paradise. Quetzalcoatl’s mythic deed seems to parallel the Promethean introduction of fire to the ancient Greeks. Just as Prometheus had incurred the ill will of Olympus, Quetzalcoatl’s generosity angered his fellow deities in the Aztec pantheon. They flayed him alive in punishment and sent forth what was left of him to wander the world as a disembodied ghost.

Quetzalcoatl promised to return, a myth that gave Cortez a brief advantage many years later, when the credulous and worshipful Aztec peasantry mistook him for their long-lost benefactor. But by that time Quetzalcoatl, for all his esteem in the imagination of the lower orders, had slipped somewhat in the regard of the ruling class: the great Aztec Montezuma and his court took their chocolate pretty much for granted and drank it mainly in homage to Xochiquetzal, the goddess of love. Among other things, it was this decadent state of affairs among the Aztec leadership that made the subjection of the Mesoamericans a pushover.

Bernal Diaz del Castillo, in his classic True History of the Conquest of New Spain, writes of Montezuma’s meals: “From time to time they brought him, in cup-shaped vessels of pure gold, a certain drink made from cacao, which he took when he was going to visit his wives.” In fact, Montezuma drank none other than chocolatl, a bitter cacao product that he considered ‘‘ambrosia for the gods.” Chocolatl was prepared by drying, roasting and grinding cocoa beans, which were then pressed into cakes after being inflamed with such spices as red peppers and chili, with perhaps a little maize thrown in. To serve, these cakes were mixed with water—latl was the Aztecan word for water, and choco described the sound made as the cocoa was whipped in a bowl. The finished product had the consistency of honey, and would be sipped and held in the mouth for a few seconds until it dissolved.

The Aztec court was so fond of this concoction that its daily intake was well in excess of 2,000 cups, with Montezuma himself accounting for 50-odd chalicefuls. Quetzalcoatl knows, he needed the energy to service his multiple wives and estimated 700 mistresses, whose demands were so strong by nature that Montezuma apparently forbade them to partake of the erethistic liquid themselves. Subsequent authorities disagree, however, as to the precise motivation of this policy: was Montezuma merely being a nasty male chauvinist pig, or was there already a fatal imbalance in the Aztec boy-girl ratio that led to an overpopulation of sexually demanding females? Were the annual mass sacrifices of virgins attempts to abate this trend? Or was Monte merely being coy, preferring to sweeten the aphrodisiacal effects of the potation with the psychological spice of the forbidden? At any rate, the women of the court did obtain their chocolatl, though not without resorting to intrigue and subterfuge. Ultimately, it was a Mexican princess named Donna Marina—”of fine figure, frank manners, prompt genius and intrepid spirit” [Diaz]—who spread the secret of cocoa to Europe.

The daughter of the prince of Painala, Donna Marina was captured by Mayan Indians and kept as a slave, until Hernando Cortez and his soldiers arrived just west of the Yucatan to begin their conquests of Mexico (or New Spain, as they called it). When the Mayas succumbed to the Europeans, Donna Marina was handed over as a spoil of war. Cortez first presented her to a lieutenant, but later took her for his own and had a son by her. Because she knew not only Mayan but also Aztec dialects, and quickly picked up Spanish, Donna Marina was invaluable to Cortez. She acted as an interpreter to both the highest royalty and the lowliest chattel.

Among the wondrous things she told him was that cocoa was valued especially highly—in fact, it was money. Cocoa beans were honored as currency throughout the markets of Mexico, and continued to be for 250 years after the conquest. Modern-day Ecuadorians still call the beans pepe de oro, “seeds of gold.” In Cortez’s day, ten beans would buy a good rabbit, a hundred a slave, and according to Bishop de Landa, chaplain to Cortez’s entourage, “He who wants a Mayan public woman for his lustful use can have one for eight to ten cocoa beans.” There was even a problem with counterfeiters who would fill hollowed-out beans with dirt and pass them off on the pre-Columbian rubes. What’s more, winked Donna Marina, cacao was the “food of the gods,” a little bit of which could make a conquistador drop his sword for a bit. Cortez wasn’t interested, though, and neither was the court of King Ferdinand, who had a look at some cocoa beans brought back by Columbus and saw in them a monumental lack of potential.

It wasn’t until Cortez entered the capital city as Montezuma’s guest in 1519 that he tried some. Sipping from golden cups in the potentate’s gilded palace, most of the Spaniards pronounced the beverage to be rank. Joseph de Acosta commented: “The chief use of this cocoa is in a drincke which they call chocolatl, whereof they make great account, foolishly and without reason, for it is loathesome to such as are not acquainted with it, having a skumme or frothe that is very unpleasant to taste.” When Cortez returned to Spain in 1521, he brought back cocoa samples, which were not immediately popular, although much of the nobility choked down the beverage for its priapic benefits. When European pirates captured a Spanish ship, though, they persisted in throwing the chocolate overboard, calling it cacuro de carnero (sheep shit).

People began to bad-mouth chocolate for reasons other than its repugnant taste. Witness Marradon, writing at the beginning of the seventeenth century: “Every kind of intercourse was prohibited between Indian women and the ladies of New Spain. The latter were accused of learning sorcery from the former, who being taught by the devil, committed an infinite number of crimes under the influence of chocolate, of which they were great mistresses.” Besides its inflammatory properties, chocolate was often cited as the medium through which Mexican witches contacted Satan.

Ironically, it was a group of nuns in a cloister at Chiapas, near the Yucatan, who changed the course of chocolate history sometime around 1550, when they mixed sugar—another new commodity—and vanilla with some powdered cocoa.

Only a few years later, the drink had become so popular locally that a bishop found himself with a congregation of women on his hands who would “pretend much weakness and squeamishness of the stomach” and thus could not sit through a Mass without a cup of the chocolate elixir. At first the bishop let these indiscretions pass, but as the habit became omnipresent, he banned chocolate outright in the cathedral. Harsh words erupted from the congregation, swords were drawn and most of the worshipers switched over to the cloister church. Soon after this, the bishop was found dead, apparently from having ingested a cup of poisoned chocolate.

The Church seemed to retain its dim view of chocolate for quite a while. Joan Fran Rauch wrote a treatise in 1624 damning chocolate as “a violent inflamer of the passions,” explaining that if certain monks had been denied chocolate “the scandal with which that holy order had been branded might have proved groundless.” As late as 1748, churchmen were arguing whether the use of chocolate violated dietary laws for pious Christians. But the work of the nuns of Chiapas could not be undone. Sweet, rich, seductive chocolate was already on its way to becoming an international habit.

The Spaniards were able to keep chocolate a secret until 1606, when an Italian named Antonio Carlette brought cocoa home from Mexico. Louis XIII of France picked up a taste for chocolate, and when his son, Louis XIV, married Maria Theresa, Infanta of Spain and a real chocolate freak, the drink became the most fashionable in the licentious French court. A contemporary writer tells us that “Maria Theresa had only two passions: the King and chocolate.”

Madame DuBarry, the lustful lady of Louis XV’s court who used everything from truffled sweetbreads to cinnamon bark to enflame the old roi, resorted to ambergris-soaked chocolate bon-bons to enable an Arabian sheik to deflower 160 maidens in a fortnight. (This feat in itself is worthy of serious consideration.)

In 1657, chocolate came to England in a big way. While not the first, the Cocoa Tree became the most famous chocolate house in England, and when it gradually became a social club, it was the foremost in England. Among its devotees were Jonathan Swift, Gibbon, and Addison and Steele, who in a 1712 issue of the Spectator, advised young ladies who wished to remain chaste to “to be careful how you meddle with romance, chocolates, novels, and the like inflamers.”

Inflamers indeed. Nearly 150 years later, the French psychiatrist, hashishin, and pioneer of psychopharmacology Jacques-Joseph Moreau, known to scholars as Moreau of Tours, described this seance of the Marquis de Sade: “M. de Sade gave a ball, to which he invited a numerous company. A splendid supper was served at midnight; now the marquis had mixed with the dessert a profusion of chocolate, flavored with vanilla, which was found delicious and of which everybody freely partook….All at once the guests, both men and women, were seized with a burning sensation of lustful ardor; the cavaliers attacked the ladies without any concealment…excess carried to the most fatal extremity; pleasure became murderous; blood owed upon the floor, and the women only smiled at the horrible effects of their uterine rage.”

That sage of the satyrs, Casanova, very often writes of employing chocolates in seduction, but he used chocolate more as a love stimulant, like champagne, rather than a chemical to produce a roomful of hemorrhaging rutters. Old Dr. Bushwhacker, a fictional rock of wisdom whose books sold widely in mid-nineteenth-century America, tells a compatriot at one point: “Tea, my learned friend, inspires scandal and sentiment; coffee excites the imagination; but chocolate, sir, is an aphrodisiac.” And only a few years back Cosmopolitan itself dubbed chocolate one of the “top ten aphrodisiacs.” So while liquor is perhaps quicker, don’t forget that candy, if chocolate, is definitely dandy.

Cosmo’s rating aside, it’s doubtful that Helen Gurley Brown or anyone else today would attribute the quality of their sex lives to the powers of chocolate. What is the difference between the killer chocolate of Montezuma’s day and the tame variety of our own? Maybe you could call it the process of civilization.

The botanical origin of Theobroma cacao is in dispute: the Amazon Basin of Brazil, the Orinoco Valley in Surinam and various other places in Central America all claim to be the birthplace of the plant. But the subsequent spread of cacao cultivation and consumption is a tale of wind and tide, luck and disaster, plunder and exploitation—in short, the history of modern economics.

Since some cocoa beans proved more psychoactive than others, our sober ancestors simply chose to breed the less potent strains. And even the civilized bean marketed today must undergo lengthy processing before it is “fit to eat.” However, current chocolate research is still trying to sort out what really happens to the many chemical components of the cacao bean during the production of commercial candy, and Dr. Philip G. Keeney of Pennsylvania State University has revealed that there are more than 300 chemical compounds in the fragrance of chocolate alone.

Theobroma is an evergreen tree cultivated not more than 20 degrees north or south of the Equator, although there are a number of flowering trees grown under controlled conditions in temperate climates. As a matter of fact, a cacao tree grows in Brooklyn—in the Botanical Gardens.

To the uninitiated, the cacao tree looks bizarrely artificial. The leaves, red when small, turn glossy green; the delicate flowers and pods grow directly from the trunk or main limbs and look as if they were tied on with No. 12 wire. The trees present a myriad of colors to the eye. Since the growth cycle is continuous, at any one time the tree will be covered with leaves, blossoms, flowers and pods of many different sizes and colors—with colorful clinging mosses, and, in some areas, small orchids and lichens completing the rainbow.

Each of the pods has 30 or 40 beans imbedded in a foul-smelling mucilaginous scum, each bean encased in a pulpy shield. The cocoa beans at this point are ivory colored and will remain so until they are harvested.

The job of picking ripe cacao pods is strictly a hand operation. The tumbadors, or pickers, employ mitten-shaped steel knives attached to long poles with which they neatly snip off the pods, taking care not to wound the tree. Once collected, the pods are split with machetes and their contents emptied out with wooden spatulas to prevent irritation from the slightly acidic pulp. As soon as the pods are split, the beans begin to oxidize to a lavender or purple hue. It is not until the beans are fermented that they acquire their characteristic chocolate richness of color and aroma.

Fermentation, or curing, serves the vital purpose of separating the bean from its adhering pulp. But in early cocoa days in Nigeria, farmers’ helpers discovered that the drippings from fermenting beans made an extremely intoxicating drink. To this day, it is no uncommon sight to see cocoa workers in Africa stretched out on the ground after a day’s work, their state not entirely attributable to exhaustion.

The curing process also reduces the bitterness of the cocoa bean and hardens the seed skin to a shell that can be easily split in the factory. Once cured, the beans must be dried. In some places the beans are polished before drying. Although polishing is usually done by machines, the cocoa workers of Trinidad still dance on cocoa beans with their bare feet to effect this extra touch. “Dancing the cocoa” is a graceful, rhythmic dance done to Calypso verses improvised around the theme of cocoa and cocoa drying.

Today, diesel-driven mechanical dryers have virtually taken over. This is unfortunate, since sun-drying is the most direct, convenient and effective method if the harvest takes place during the dry season. Before mechanization, all cocoa beans were dried in the sun, spread out on palm leaves or large wooden trays that could be covered in the event of rain, to prevent moisture from rotting the beans. The lyrical Trinidadians have a saying, “Ah ent got cocoa in the sun, so ah ent lookin’ for rain.” Which means, approximately, “I don’t give a fuck.” Modern international chocolate cartels have a less colorful respect for so unstable an economic force as rain. Time marches on.

Eighty per cent of global chocolate output comes from the “Big Five”: Ghana, Nigeria, Brazil, the Ivory Coast and Cameroon. The growing countries generally keep no more than 10 per cent of their crop for home use, usually less. The five giant processing countries—the United States, West Germany, the Netherlands, the U.S.S.R. and Great Britain—account for over half the cocoa processed worldwide, with western Europe and North America consuming a full 70 per cent of the annual cocoa product. In recent years, the biggest forward strides in cocoa consumption have been taken by the communist countries and Japan because of liberalization of government import restrictions. In 1960, the Soviets consumed 74,000 tons of cocoa beans, compared to the 215,000 tons scarfed down in the U.S. By 1970, the figures accelerated to 182,000 tons and 261,000 tons respectively. Japan now consumes five times the amount of cocoa it did in 1960 and has recently introduced chocolate-flavored honey into the world market.

American chocolate production and consumption figures are not revealed to the public, for whatever stealthy reason. We know that the U.S. processes 261,000 tons of cocoa beans annually, most of which we consume ourselves. But cocoa beans are included in thousands of products in varying concentrations, so it is hard to extrapolate from these figures exactly how much chocolate Americans eat.

We do know that confection sales by U.S. candy manufacturers top $2 billion yearly, and spokesmen for the confectionary industry report that chocolate products account for 60 per cent of this total. The average American consumes 18.7 pounds of candy per year, and, applying the same 60 per cent proportion for chocolate, we can readily approximate that 3.4 ounces of chocolate are eaten by each person in the U.S. weekly. This is hunger somewhat below the European average of four ounces a week. The Swiss probably take the chocolate-eating cake, yodeling down over five and a half ounces weekly per capita. Although consumption figures are not available for the U.S.S.R., one new Moscow factory is turning out 32,000 tons of chocolate annually, and many more tons are imported.

A personal survey of candy wholesalers revealed the top-selling chocolate candies in the U.S. to be, in no particular order, O. Henry, Hershey’s Milk, Peter Paul Mounds, Chunky, M & M Plain, Three Musketeers, Nestle’s Crunch, Kit Kat, Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups and Hershey’s Rally Bar. Two former biggies, Clark Bars and Baby Ruths, are dying on the east coast. And perhaps due to inflation, boxed candy and miniatures, too, have been falling off in sales.

Dropping in sales, perhaps, but dropping out of fashion? Never. A visit to a chi-chi chocolatier will reveal a cornucopia of tasty miniatures, from a half-pound of Bartons for $1.50 to a custom-made velvet box containing a pound of chocolate for which bidding opens at a cool $100. If your taste runs to crystal goblets, double that figure. But if the packaging matters not, New York’s best boxed chocolate, including Godiva, Krön, Corne de la Toison d’or of Belgium and Le Notre of France, can be had for a scant $9 per pound.

If this seems a little steep, the neophyte chocophile can keep it simple and start with the proletarian chocolate bar. The first decision, of course, is which brand. Harry Levene, of London might be of some help—he’s known as the Chocolate Wrapper Collector, and as of the end of December 1974, his collection held 30,174 wrappers from different chocolate bars made all over the world.

After that, it’s a fairly simple matter to choose among milk, dark, Swiss, Dutch, semisweet, bittersweet, or extrabittersweet; of course, some may choose to suck on unsweetened, or baker’s chocolate, but that is entirely optional. All that remains to be done is to select from hazelnut, raspberry cream almonds, mint, walnut, truffle cream, peanut, rice, freeze-dried strawberry, orange peel, chocolate cream and about 40 other possible mates for King Chocolate bar form.

Once we leave the modest bar, the fillings become yet more exotic. Every kind of fruit and nut center is obtainable. The booze hound can revel in the taste of chocolate rum, sherry, cognac, and creme de menthe cordials. The true cirrhosis fancier can purchase martini olives, a martini-flavored liquid center encased in chocolate and covered with a thick, olive-colored shell. Ants, shredded coconut, hashish, marshmallow, bees—it’s likely that someone has at some time covered dirt with chocolate and found it tasty.

If you prefer form over content, chocolate can be molded into the shapes of chrysanthemums, shrimp, apples, hearts, “kisses,” scallops, “lace,” bunnies, turtles, and thousands of equally cuddly configurations. Bloomingdale’s department store in New York sells a two-foot oval cameo of pure chocolate, complete with candy-drop earring, for $12.50. Droste, the Dutch chocolatier, exports solid chocolate initials, which lowlands lovers traditionally exchange on December 5, St. Nicholas’s Day.

There are a number of chocolate specialists who will mold chocolate into any shape for a price. If that shape involves producing a new mold, the price is well over $1,000. However, a new process has been developed for those seeking the personal touch at a reasonable price. Now, for under $20, you can have any photograph or piece of art reproduced in dark chocolate on a white chocolate disk similar in appearance to a lollipop. (White chocolate, incidentally, has no cocoa butter and is therefore not really chocolate. Vegetable oils are the flavorings used to produce its chocolatelike flavor.)

Most custom molding is done for commercial promotion gimmicks— chocolate jumbo jets, pianos, clocks, baseball bats—but there survive a few true chocolate artists. Richard Mack, food coordinator at a Dallas luxury hotel, uses no special tools, just sharp kitchen knives, to turn out his masterpieces. They have included eight prancing reindeer for a Christmas party, a five-inch fawn, numerous busts of French notables of the Louis XIV period, a Mack truck and a five-foot Easter egg. Current holder of the First Prize for Chocolate Work at the Annual Salon of Culinary Art and Exhibition of New York City is Guy Lucas, whose four-foot chocolate Mickey Mouse beams out the window of an exclusive Manhattan chocolatier.

In 1975, chocolate has been tamed. Its alkaloids no longer convulse nunneries, intoxicate maidens or reinforce limp polygamists. The trickle of chocolated orgy making has become a mighty river of middle-class tooth decay; the chocolate of today melts in our mouths, not in our minds. Chocolate, which once made men mad, has gone soft from prudish breeding, industrial conditioning, commercial packaging and easy living. Perhaps, of all the fabled psychedelic alkaloids of the world’s remote lotus-eaters—the caffeine, the theine, the theobromine, beside which the distilled juices of the grape and the potato once paled— only cocaine remains, toxic, mesmeric, incandescent, waiting to be brought into the fold and onto the supermarket shelf in the form of coca bars, coca yogurt, coca liquers, coca bathroom disinfectant and all the rest. . . . Only time will tell.

The post Flashback Friday: The Deep Dark Secrets of Chocolate appeared first on High Times.

Comments

Comments are disabled for this post.