By Leslie Stackel

Conservative voices have held sway over talk-radio’s airwaves since the 1960s, selling a backlash against progressive ideas to a frightened public married to the status quo. How did it happen? Why does it continue, and where can someone tune in to hear a voice taking the liberal or, heaven forbid!, leftist position on political issues?

A year after comedian Al Franken published Rush Limbaugh Is A Big Fat Idiot (Thorndike Press, Thorndike, ME), the obese sultan of right-wing talk radio still rules the airwaves. Limbaugh and his ultraconservative cronies, most notably G. Gordon Liddy and Ollie North, rant continuously against “feminazis,” environmental “wackos,” minorities and all things progressive in a rolling firestorm of sock-it-to-’em hate radio. Their brand of vitriol has earned them over 600 station spots, mostly Rush’s, on nationally syndicated radio, reaching more than 20 million listeners. And despite reams of bad press, reproach from more moderate Republicans and sagging ratings, the Limbaugh ilk continue to infect our country’s talk-radio continuum like a bad flu it can’t shake.

Where will the cure for this epidemic virus come from? Where can the long-suffering listener tune in for a liberal shot in the ear? Who will present a balanced sensibility for the other side, and an overdue public hazing of Limbaugh and his prating dittoheads?

According to Michael Flarrison, editor of a broadcast publication called Talkers Magazine, talk radio isn’t entirely a conservative wasteland. Dozens of liberals can be found around the dial on local stations, he contends. “About 40% of radio dialog is liberal,” he estimates, “but the media have played up the rightists.”

Maybe. But his 40% figure pretty obviously depends on one’s definition of “liberal.” In one recent study on talk radio by the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg School of Communications, for instance, such political talking heads as former New York Mayor Ed Koch and Washington, DC centrist Diane Rehm were somehow deemed “liberals.” By any reasonable definition, one is hard-pressed to find any nationally recognized leftist name in talk radio these days. Harrison concedes there is no Limbaugh of the left, no “national superstars with devoted followings.”

Dial around, though, and two likely candidates begin to emerge from the static. Jim Hightower, a former Texas state agriculture commissioner, is a populist hell-raiser from Austin whose sharply twangy political assaults and sly humor (as in his regular “Hog Report,” covering “pork” in government dealings and big business) have fetched him a 100-station listening public “from Maine to Maui” since 1991. And there’s Tom Leykis of Los Angeles, a rousingly souped-up, no-holds-barred, left-leaning political riffer with the flair of an AM-radio DJ. Leykis spares no one during his four-hour afternoon broadcasts on Westwood One radio, syndicated to 220 other stations, and he’s been working at it for 26 years. Former California Governor Jerry Brown may have more name recognition than either of these on-air personalities, but his “We The People” program is broadcast strictly over Pacifica nonprofit radio, limited in market scope.

However, neither Hightower nor Leykis, the two top-rated lefties, can be heard in New York City, or in very many other big-city radio markets—an absence not entirely accidental. Jim Hightower briefly broadcast his show over the ABC radio network before 1995, when it was summarily canceled without warning—immediately after word leaked of a planned merger between Disney and Capital Cities, which owns ABC. Despite drawing a sizable audience, Hightower was dropped from the network lineup, presumably for his outspoken criticism of this Mickey Mouse merger and the new Telecommunications Act that permitted it, aside from his regular muckraking features aimed at corporate America.

The Mouse That Censored

ABC claimed insufficient ad revenue as an excuse for the cancellation, but Hightower points out that the network neglected to pursue his best identifiable source for sponsorship and ad dollars—labor unions. In fact, ABC rejected one union’s $20,000 offer to buy ad space, and dismissed all others as “advocacy advertisers,” unacceptable as commercial supporters. (Of course, the network would never consider that the corporate funders of their more conservative shows might harbor a political agenda, would they?)

Which raises the question whether leftslanted, populist talk radio is mutually exclusive with broad-scale commercial success. Hightower seems poised to discover the answer. Since mid-1996 he’s been airing a new call-in program from Austin’s downtown Chat & Chew restaurant over United Broadcasting, formerly known as the People’s Radio Network. With his unshakably leftist politics, he might serve as an ideal test case for progressives everywhere.

As Hightower points out, “We’re definitely about naming names. Unlike most liberal radio hosts, I don’t just talk about vague, social causes of things, but really focus on corporations, and do it by name. When taking on an issue, we go at it in terms of who’s putting up the money for the policy that’s involved with the issue.”

United Broadcasting, Hightower explains, funds itself essentially by acting as “a marketer of made-in-the-USA products. They’re like a Home Shopping Channel, so they’re not at the mercy of big brand-name advertisers.” Co-owned by the United Auto Workers union, founded by libertarian Pat Choate—a former Ross Perot running mate—the network is nothing if not political. With a nod to the current stagnant wave in radioland, United has signed as its other on-air celebrity, ironically, Bay Buchanan, Pat Buchanan’s sister.

Micropower to the People

Things are not likely to get much better before they get even worse, either, with Newt Gingrich et al slashing federal funds from National Public Radio, calling their studiedly neutral tone “too liberal.” Even lower-profile, listener-supported broadcasting venues are gradually caving in to conservative pressure, such as the five-station, 50-affiliate Pacifica Network.

Federal attacks on their funding base have predictably prompted internal power struggles at some of these stations, further threatening their progressive programming. At Pacifica’s home-base station, KPFA in Berkeley, CA, the board of directors in 1994 purged the most radical voices and installed a slicker, more “professional” corporate-style management team. Now there are similar tugs-of-war raging at both KPFK in Los Angeles and WBAI in New York City—Pacifica’s flagship and longtime bastion of community activism and free speech. All this is leading left-wing talk radio in only one direction, say observers: underground.

“I see progressive voices on radio being forced underground, and I see pirate radio spreading all over the country, which is both good and bad,” says HIGH TIMES editor-at-large Bill Weinberg, cohost of “The Moorish Orthodox Crusade” on WBAI (a mix of anarchist political analysis and pop culture that he says is “hanging by a thread”). “Bad because when underground, things get more precarious and fewer people get to hear it. And good because being underground is purer and keeps you in that hardcore adversarial spirit, which has been eroded by progressive radio being on the federal teat for so long.”

Stephen Dunifer, an outspoken leader of the unlicensed pirate-radio movement, founded the rebel station Free Radio Berkeley in 1993. Dunifer says he was driven to defy the Federal Communications Commission by a mixture of factors: the Reaganite political climate of the 1980s and early ’90s; media coverage of the Gulf War and other foreign issues by press release and sound bite, and by the abandonment of local grass-roots activism on Pacifica’s stations.

The final straw came in 1993, with KPFA’s muting of Dunifer’s friend Dennis Bernstein, after Bernstein had challenged the mayor of Berkeley’s claim that she’d had no involvement in mobilizing a police riot squad during a protest that year in People’s Park. During an on-air interview, Bernstein produced some of the mayor’s correspondence, procured via the Public Records Act, between her and the UC Berkeley chancellor, proving they’d worked together “hand in glove” during the police action.

“She freaked out on the air,” says Dunifer. “Two weeks later, Dennis gets a message from the station manager saying ‘lay off the mayor.’ Very clearly, we were dealing with an established progressive-liberal political machine.” KPFA was no longer “the people’s station,” and so Dunifer set up Free Radio Berkeley at 104.1 on the dial to fill the void.

Dunifer and other radio rebels “are reacting to a situation in their areas, where public radio is not quite as public as it’s supposed to be,” says Estelle Fennell, news director of KMUD (91.1 FM), a community station in Garberville, CA, 200 miles north of Berkeley. KMUD, she acknowledges, is “unique” in its independence at a time when all traditional alternatives to mainstream media are failing their listeners. “College stations are tied in to college politics,” she observes, “and too many community stations are tied in to a kind of polish and topdown mentality,” leaving activists with little choice but to seek other outlets.

KMUD, Fennell contends, exemplifies the necessary alternative—stations committed to their local listeners, regardless of the risk. Located in Humboldt County, a heavy potgrowing area, KMUD routinely airs up-to-the-minute reports and warnings of helicopter raids of growers’ fields—some while in progress—to the ire of regional cops and federal DEA agents. Apart from a few other stations “like KAOS in Seattle,” she says, “I can’t think of many other local [licensed] stations with a good, committed, free attitude.”

But others do exist, on both coasts. Chuck Rosina of Boston, the news director at MIT’s college station, WMBR (88.1 FM), is a hardcore homeless-rights advocate. On his own two-hour show, “No Censorship Radio,” Rosina says he generally pushes the limits of free speech on the Pacifica affiliate, and suggests management “looks the other way so long as we don’t get major complaints.”

At his home studio, “W Bla Bla Bla,” though, Rosina puts together show segments for general distribution, often collaborating with “pirates” from Boston and Berkeley, and in these projects, “no censorship” is the guaranteed uncompromising rule.

Stephen Dunifer, elaborating on Bill Weinberg’s comments, says massive numbers of independent thinkers and activists are turning to outlaw radio. The preferred term is “micropower broadcasting,” since pirate radio uses low wattage compared to commercial enterprises, and it’s been “popping up everywhere around the country.” Dunifer estimates about 400 stations now exist border-to-border. On the West Coast it’s rampant, and elsewhere as well its guerrilla reporters and interviewers are frontline activists, not just talking heads.

In Texas, the three politically-minded co-founders of Kind Radio San Marcos (105.9 FM), southwest of Austin, for example, gained a degree of notoriety as members of the San Marcos Seven, a group that was arrested and served short jail terms in 1991 after a spontaneous pot smoke-in at the Hays County Jail. Their pirate operation, begun last March, features irreverent coverage of pot use and legalization, plus other timely and often taboo issues via news, interviews, talk, radio theater, poetry and music. “We devoted an entire ‘Common Sense’ call-in show to people’s first experiences with marijuana,” recalls co-founder Joe Ptak. Setting up and running a micropower station, he says, “is easy and fun.”

Even more ambitious in stamping out censorship is Free Speech TV, the Boulder, CO alternative-programming service which packages and distributes shows to about 70 cable and public-access TV stations nationwide, and runs a website (www.freespeech.org) using material from both pirate and licensed radio. “We believe in the aim of micropower radio, to take the airwaves away from the powers that be,” says Web editor Joey Manley. “We use stuff from people like Napoleon Williams of Black Liberation Radio in Detroit, who’s currently embattled in disputes with the FCC, and some other microstations.” This material is mixed in with great legit radio, like Mike Thornton’s “Full Logic Reverse” on KVMR in Nevada City, CO. “Any issue the left champions doesn’t get access to the media,” Manley notes. “What we want is to get these ideas into the mainstream of society.”

Getting organized is key, insists Paul Griffin, a Free Radio Berkeley show host and founder of the Association of Micro-Power Broadcasters. He urges folks to get involved with the group, and to attend the annual conference for micro proponents, held this year in Carson, CA.

FCC You, Limbaugh!

Free Radio Berkeley made history last April after winning a precedent-setting court case brought when the FCC tried to shut it down. Federal District Judge Claudia Wilken refused to grant the commission an injunction to close the rebel radio operation, the first repulse ever for the FCC in such a case, pointing out that “there were real constitutional questions here that should be resolved in a trial,” according to Dunifer. Mostly those questions revolve around obvious First Amendment free-speech issues.

Dunifer expects that the FCC’s second motion to cut off the station, now awaiting a ruling, will keep the case in the legal system till around the year 2000. By then, the micropower movement should be flourishing. Like all radical action, this systematic movement could influence and even empower mainstream, liberal and left-leaning “legitimate” broadcasters.

Meanwhile, progressives in commercial radio are busy trying to compete with the tidal wave of conservative on-air hosts, striving to bowl over both listeners and station owners through style as much as substance. Pumping up listenership for these alternative hosts, though, often means learning to switch frequencies—not in terms of airwaves, but in their on-air personality and general modus operandi.

Tom Leykis, for one, believes that before station owners will come calling, progressives have to disprove the sticky myth that liberals make for boring radio.

“See,” he says, “Limbaugh has convinced people that no liberal is entertaining. There’s some truth in that,” he jokes, “but it’s not 100% true.” Moderates are all too often, by definition, moderate: “A lot of liberal hosts are afraid to take stands,” diagnoses Leykis, “’cause they’re afraid of offending people. You get all these nice liberals saying, ’Well, I can understand on the one hand how people would feel this way, and on the other hand how they’d feel that way’, like NPR, which induces coma.” Radio hosts, he insists, “have to be willing to get down in the mud with anyone” and “not afraid to take quotable, sound-bite stands.”

A one-time music DJ and stand-up comedian, Leykis says that what ultimately makes a gab-show zing is plain entertainment, not political discourse slanted either left or right. Political advocacy, he reckons, is secondary. And the fact that Rush Limbaugh’s megasuccess as an entertainer has been matched by neither liberal nor conservative stands as proof of Leykis’ canny insight.

Whatever the formula for success in commercial radio, cracking the current conservative hegemony on call-in shows won’t be easy, says Steve Randall, senior analyst and resident talk-radio expert for FAIR (Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting). Historically, he explains, “Political talk radio arose as a major phenomenon in the 1960s, and the first star of the form was Joe Pyne on KABC, who was considered a real hatemonger. Talk radio in those days was a bunch of white guys on the right railing against the civil rights movement, the anti-Vietnam War movement, women’s liberation and so on. It was born in backlash, and has been that way for 35 years.” By now, Randall says, right-wingers have well-paved inroads: “They’ve cultivated an audience who are used to their ideas, their political viewpoints, and what they consider humor.” Liberals have to do the same.

Jim Hightower says liberal voices are on their way. People are obviously getting tired of Limbaugh: “He’s becoming boring and he’s essentially out of material, because he spends all his time on the air just attacking Bill Clinton and defending Newt Gingrich. He’s become the national press spokesman for the Republican Party.” Folks, he believes, are ready for real populism on the airwaves, not the “faux populism” of Rush. As for his kneejerk copycats, they’re losing not only credibility but ratings. In fact, notes Hightower, “If it weren’t for the Christian networks, Ollie North would be long gone.”

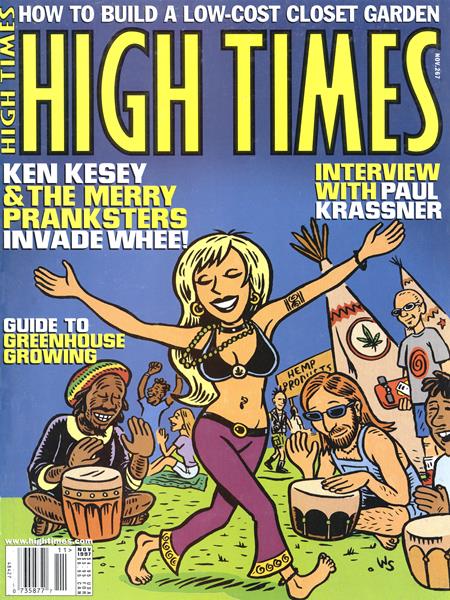

Read the full issue here.

The post From the Archives: Hello, is anyone out there? (1997) appeared first on High Times.

Comments

Comments are disabled for this post.