Everyone knows psychedelic rock began in San Francisco with bands like Jefferson Airplane, The Grateful Dead, and Quicksilver Messenger Service. Few people, however, recall an even earlier group that became a major attraction in the Bay Area in 1966: the CHOCOLATE WATCH BAND.

Although the WATCH BAND never had a hit record, never achieved national recognition, and never got invited to Woodstock, they spawned a devoted cult following that grows larger each year (despite a notable lack of publicity or record company hype.) The band released only three albums, yet 15 years after their release, two of the records continue being re-issued, with original copies trading hands for as much as $75.

Why does this group refuse to die?

To find out, I decided to locate the WATCH BAND’S lead singer, DAVID AGUILAR, who as far as I knew, had never been interviewed before. I hardly knew where to start. My only lead was a rumor he was teaching astronomy at a Colorado University.

The rumor turned out to be true—sort of. After several phone calls, I discovered someone named Aguilar had formerly been in charge of a Colorado planetarium, but had left the academic world for a more lucrative post elsewhere. After a few blind calls, I eventually tracked down a David Aguilar working for an aerospace firm.

“Is this the same David Aguilar that used to sing with the Chocolate Watch Band?” I asked tentatively.

There was a brief pause, followed by an amused chuckle. “Yes, it is,” answered the voice.

Aguilar seemed genuinely surprised anyone remembered his former life as a rock star. I asked if he was aware of the Watch Band’s growing popularity—evidenced by the release of several new compilation albums. “Yeah, I saw some of the re-issues in a record store,” he replied. “But until I saw them, I didn’t know they existed. I never received a penny from any of our records.”

I next asked if Aguilar had any sixties memoribilia, mentioning I was particularly interested in a legendary box the band had always carried with them, a box reportedly filled with every conceivable variety of mind-altering substance. (Their producer Ed Cobb described the box on the back of a greatest hits album released in 1983: “[It] was incredibly hand-tooled, hand-carved, inlaid wood, like a giant fisherman’s box. In it were sticks of hashish close to a half-inch in diameter, LSD, and all the pills you could imagine! … The smoke was so heavy coming underneath the [studio] door that I had a contact high for three days!”)

“I don’t know what happened to the box,” laughed Aguilar. “Maybe it beamed directly into space after a recording session.”

In a later conversation, Aguilar confessed he was the only member of the group who wasn’t into drugs. He also explained why he’d gotten rid of many vestiges from his past. “I threw everything away from the sixties, even my records,” he said. “I still have a lot of bad feelings over what happened to us during those years. The flower child era was a magical time, but most people don’t realize how brief it really was.”

In these dark days of MTV-style shlock rock, it’s hard to believe there was a time when almost every kid in America felt he had a shot at becoming a rock star. The lawyers, accountants and image makers were around, but hadn’t quite figured out how to run the system. Consequently, phony posturing, rock star cliches, and designer haircuts were kept to a minimum.

The American garage band movement began in the mid-sixties largely as a reaction to the British invasion.

By the early sixties, America-made rock had already been undermined by a procession of baby-faced Fabians and Frankies, and the British had no trouble taking over the scene when they reverted to the original spirit of Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Bo Diddley, etc. Most American garage bands formed as copy bands imitating the British sound. It was a weird time—what with the Brits imitating the Blacks and the Yankee teenagers imitating the Brits. The emphasis was on three-chord dance songs anyone could play, and the action centered around high school hops and fraternity parties. Some groups were pop oriented (meaning they sounded like the Beatles), while others pursued a more demented sensibility (meaning they sounded like the Rolling Stones).

Unlike today, the teens of the sixties were actively rebelling against a hypocritical society whose value systems had collapsed. Consequently, garage bands and drags were a natural combination. The earliest bands probably ranked alcohol highest on the preferred list of mind-altering chemicals, but others were into more exotic highs, such as smoking paregoric, sniffing glue, or popping the occasional diet pill stolen from mommy’s purse. Marijuana was just coming into vogue in 1964, but it was the arrival of LSD that really pushed the garage band sensibility to unexpected realms.

Acid, as it turned out, did not mix well with your typical teenage rock ’n’ roller. Acid heads tended to be gentle, introspective creatures, while garage bands were violent and destructive. Not many bands could combine the two sensibilities, and those that did, didn’t last long. In fact, the fusion of punk and psychedelia is so unstable that the Watch Band have remained one of the few groups to successfully pull it off.

• • •

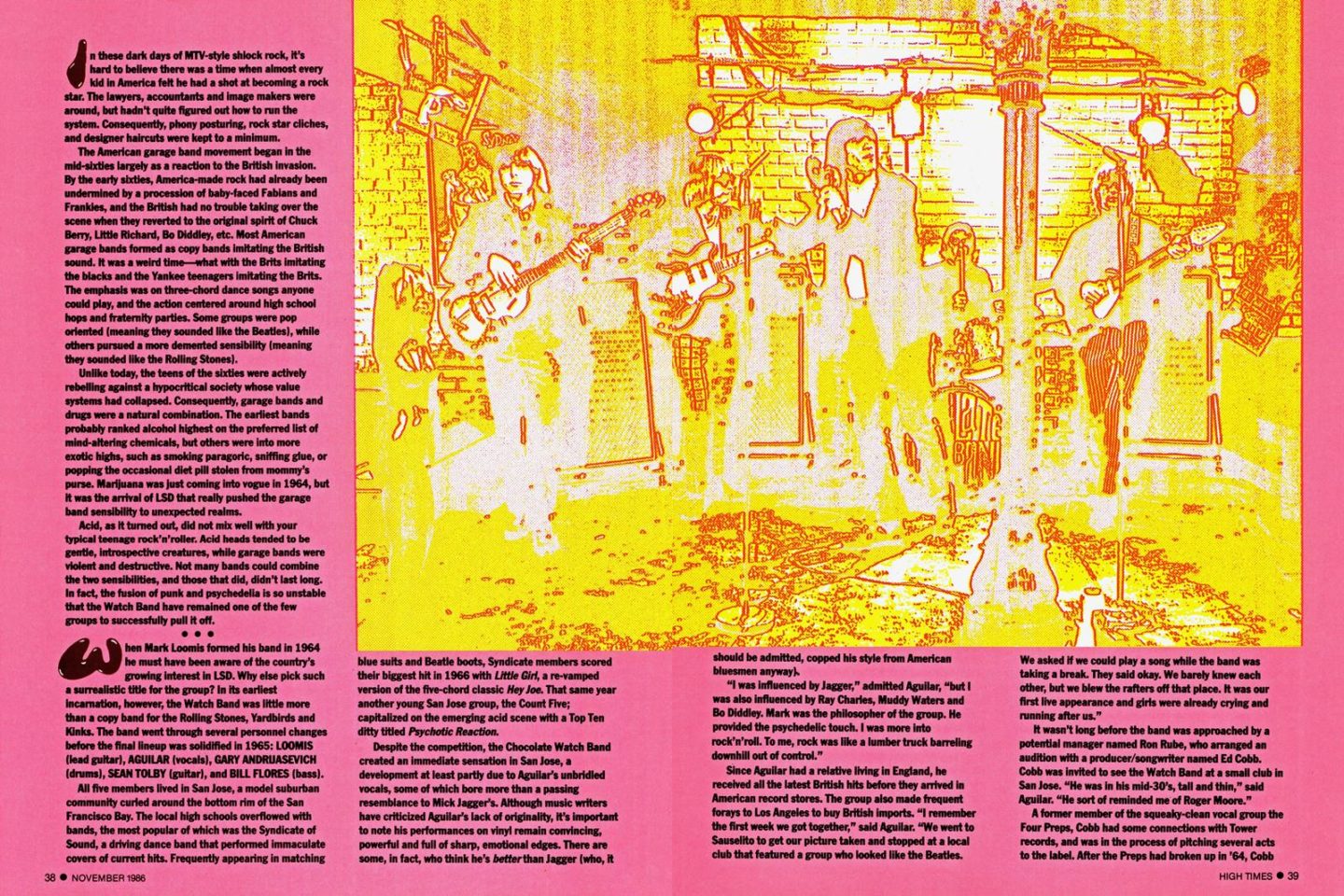

When Mark Loomis formed his band in 1964, he must have been aware of the country’s growing interest in LSD. Why else pick such a surrealistic title for the group? In its earliest incarnation, however, the Watch Band was little more than a copy band for the Rolling Stones, Yardbirds, and Kinks. The band went through several personnel changes before the final lineup was solidified in 1965: LOOMIS (lead guitar), AGUILAR (vocals), GARY ANDRUASEVICH (drums), SEAN TOLBY (guitar), and BILL FLORES (bass).

All five members lived in San Jose, a model suburban community curled around the bottom rim of the San Francisco Bay. The local high schools overflowed with bands, the most popular of which was the Syndicate of Sound, a driving dance band that performed immaculate covers of current hits. Frequently appearing in matching blue suits and Beatle boots, Syndicate members scored their biggest hit in 1966 with “Little Girl,” a re-vamped version of the five-chord classic “Hey Joe.” That same year another young San Jose group, the Count Five, capitalized on the emerging acid scene with a Top Ten ditty titled “Psychotic Reaction.”

Despite the competition, the Chocolate Watch Band created an immediate sensation in San Jose, a development at least partly due to Aguilar’s unbridled vocals, some of which bore more than a passing resemblance to Mick Jagger’s. Although music writers have criticized Aguilar’s lack of originality, it’s important to note his performances on vinyl remain convincing, powerful and full of sharp, emotional edges. There are some, in fact, who think he’s better than Jagger (who, it should be admitted, copped his style from American bluesmen anyway).

“I was influenced by Jagger,” admitted Aguilar, “but I was also influenced by Ray Charles, Muddy Waters, and Bo Diddley. Mark was the philosopher of the group. He provided the psychedelic touch. I was more into rock ’n’ roll. To me, rock was like a lumber truck barreling downhill out of control.”

Since Aguilar had a relative living in England, he received all the latest British hits before they arrived in American record stores. The group also made frequent forays to Los Angeles to buy British imports. “I remember the first week we got together,” said Aguilar. “We went to Sausalito to get our picture taken and stopped at a local club that featured a group who looked like the Beatles. We asked if we could play a song while the band was taking a break. They said okay. We barely knew each other, but we blew the rafters off that place. It was our first live appearance and girls were already crying and running after us.”

It wasn’t long before the band was approached by a potential manager named Ron Rube, who arranged an audition with a producer/songwriter named Ed Cobb. Cobb was invited to see the Watch Band at a small club in San Jose. “He was in his mid-30’s, tall and thin,” said Aguilar. “He sort of reminded me of Roger Moore.”

A former member of the squeaky-clean vocal group the Four Preps, Cobb had some connections with Tower records, and was in the process of pitching several acts to the label. After the Preps had broken up in ’64, Cobb had formed a production company called Green Grass with an old friend, Ray Harris. The duo was determined to mine the new emerging youth market. (Cobb’s final recording with the Preps had been titled “A Letter To The Beatles.”) Cobb had already written a song titled “Dirty Water” and was looking for a group to record it. His first choice was an LA garage band called The Standells.

“The Standells were a good studio band,” said Aguilar, “but they were terrible on stage. I’m still upset we didn’t get ‘Dirty Water’ because we could have had fun with that song. Cobb gave it to The Standells because they had a Farfisa organ.”

While “Dirty Water” was climbing the charts on its way to becoming a massive national hit, Cobb went to work on another song for the Watch Band titled “Sweet Young Thing.” First, however, the band was asked to sign a multipage contract with Green Grass. “Our manager told us it was a really good deal,” said Sean Tolby in 1983. “But it was awful! They owned our name, they owned everything! On Rube’s word, we signed it without realizing what would happen.” “We were only 17 and 18 years old,” added Aguilar. “Cobb said he’d make us stars. We didn’t know what we were doing.” (Within a matter of months, the group would get much better offers, including one from Filmore owner Bill Graham, but by that time it was too late. They were locked into a five-year contract.)

Released in ’65, “Sweet Young Thing” promptly went nowhere, which is strange since the song is considered something of a classic today. Aguilar blames Tower. “I don’t know why they put us on that label,” he said, referring to the fact Tower passed the tape to Uptown, a Black R&B subsidiary. Obviously, the record’s promotion was botched.

“It was a marvelous beginning,” writes archivist Brian Hogg of the song, “somewhat modeled on The Standells, but with a prominent Rolling Stones influence in Aguilar’s Jaggeresque phrasing, the Brian Jones harmonica and the guitar riff, which somehow always seems to be hinting at the tune of ‘Paint It Black.’ ‘Sweet Young Thing’ is, however, more than mere cloning, there’s an atmosphere that’s purely Californian that makes it special.”

Cobb was dividing his time among many projects and with the success of The Standells, he had less and less time for the Watch Band. “We saw very little of him,” said Aguilar. “We were on tour all the time.” Cobb began to view the Watch Band more as an outlet for cashing-in on the psychedelic subculture. Unfortunately, his efforts to realize this goal would usually be made at the band’s expense.

“One day Cobb called us and told us to fly down to LA to be in a movie,” said Aguilar. The result, Riot on Sunset Strip, provides the only known footage of the Watch Band performing. Unfortunately, they were forced to lip-sync, performing two highly derivative originals that were probably written on the spot: “Don’t Need Your Lovin’” and “Sitting Here Standing.” As far as Aguilar is concerned, the true sound of the band was never captured on film or vinyl. The film, however, does offer a sample of the band’s impressive stage presence.

The Watch Band was especially appreciated at San Francisco’s Fillmore Auditorium, where they shared the bill with such acts as The Yardbirds, The Mothers of Invention, and Jefferson Airplane. They also performed as an opening act for The Seeds, a band they considered their musical inferiors. To show their disdain, they opened with 25 minutes of Seed covers, including the hit “Pushin’ Too Hard.” “The Seeds were so mad they didn’t want to come out and play,” laughed Aguilar.

Meanwhile, according to Aguilar, Loomis and Tolby were sinking into a psychedelic haze. “I think LSD really messed them up,” he said. “It opened a few doors that probably should have been kept closed. There were nights when our equipment manager would have to stand behind Sean and prop him up. I was afraid to take acid because I saw so many burn-outs.” On a trip to LA, Loomis bought a polished mahogany box with brass fittings and filled it with drugs. “It became his first aid kit,” said Aguilar.

Despite a lack of airplay or media attention, the Watch Band had high hopes for their first album No Way Out, which was released in September 1967. Half the album was given over to Cobb’s concepts, even though the band had already proven their songwriting abilities. Cobb insisted on two covers, “Hot Dusty Road” and “The Midnight Hour.” The third cover, Chuck Berry’s “Come On,” was more representative of Aguilar’s taste. The Watch Band contributed three originals, including “Are You Gonna Be There (At the Love ln),” which remains one of the finest anthems to emerge from San Francisco. While other groups were falling into a quagmire of hippie idealism, the Watch Band were translating the acid experience into an us-versus-them teen drama.

“Too many people don’t know where they belong,” sang Aguilar. “They need someone to tell them right from wrong. You better break away. Try to be yourself. Don’t leave your future to someone else.” Loomis’ mindwrenching guitar riffs are reminiscent of the best work done by Jorma Kaukonen of Jefferson Airplane. But then, the two were friends and probably arrived at the sound simultaneously. The other two Watch Band originals were “No Way Out,” a masterpiece of early psychedelia, and “Gone and Passes By,” a sitar rave-up with a Bo Diddley beat.

However, when the album was released, the liner notes mysteriously failed to mention the band members by name. Even worse, the band had never even heard three of the songs, which were performed by studio musicians. One of these, “Gossamer Wings” was an obvious re-write of an earlier single written by Aguilar and Loomis titled “Loose Lip Sync Ship.” “Gossamer Wings” was credited to Don Bennet and Ethan McElroy, and the vocal was performed by Bennet. The other two Cobb creations, “Expo 2000” and “Dark Side of the Mushroom” attempted to cash in on the Watch Band’s druggy image. “Expo 2000” was a good song, but why didn’t Cobb tell the band about it or let them perform it themselves?

“We submitted two album cover designs,” said Aguilar, “and they said they’d use one of them. But the album came out with a completely different cover. I came to the conclusion we were going nowhere.” Aguilar was so upset he temporarily left the group.

Cobb, however, convinced everyone to get back together for a second album, promising things would be different. He was right. For the second album, things got worse. All pictures of the band and mention of names (except for Cobb and his studio cronies) were left off, and Cobb took over an entire side for his own psychedelic experiments.

“They were trying to convince us they didn’t want anyone to see what we looked like until they saw our concerts,” said Sean Tolby in a Goldmine interview in 1983. Apparently, Cobb had convinced some members of the band this strategy of not giving the band credit would create a mystique around the group. A more likely scenario, however, was that Cobb was keeping his options open, while holding the band in the worst possible bargaining position. Shortly after the record was released, Aguilar left the group for good, taking much of the fire driving the band with him.

“The Chocolate Watch Band had broken up and come together several times,” Cobb told an interviewer in 1980. “I really enjoyed working with them, but they had no rules binding themselves. Consequently, they would break up. It didn’t matter if they were successful or not. Then I would talk to them, and they would agree to do something else. By the time of the third album, they had developed to the point where they were so strong together, that I would have been a fool to have my influence be in there and screw up what they were trying to do.”

“More likely Cobb saw a tired group,” wrote Brian Hogg. “The resulting album One Step Beyond was a great disappointment. The group wrote most of the songs, the one cover being ‘I Don’t Need No Doctor’ which never lifts off, and the rest are rather ordinary. ‘Uncle Morris’ was good, ‘Flowers’ had its moments and ‘Devil’s Motorcyle’ was interesting if only for its guitar work, supplied by an incognitio Jerry Miller of Moby Grape.”

However, by 1969 the bottom was dropping out of the psychedelic exploitation market, and Cobb was predictably losing interest in the genre. He gave the band a free hand at last, but it was two years and two albums too late. Without Aguilar, the group wasn’t complete, and Loomis was so high he couldn’t perform his solos.

“Performing in front of 20,000 screaming fans is the greatest high in the world,” said Aguilar. “I was really sorry to see that taken from us. I still miss it.”

Read the rest of this issue here.

The post From the Archives: The Chocolate Watch Band (1986) appeared first on High Times.

Comments

Comments are disabled for this post.